Polymers having “conjugated structures”,

allowing them to conduct electricity, hold great potential for flexible and

ink-jet printable electronic devices

and inexpensive plastic solar cells. Work

by Hayward and Emrick

in the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) on Polymers at

the University of Massachusetts Amherst has shown how to coax such polymers to

twist into conducting wires thousands of times smaller than the twisted cables

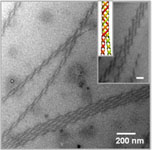

used in common electronic devices. These structures are based on polythiophenes, which tend to crystallize into ribbons

only a few nanometers in thickness. Such crystalline nanostructures are

important to determining the electronic properties of materials based on this

polymer, and the ability to control their formation holds promise for improving

the performance of devices. Remarkably, the inclusion of functional groups that

bind salt ions leads to twisting of these nanowires into helices that join

together into double helices, reminiscent of DNA, and larger bundles containing

multiple strands. These materials provide opportunities to 1) study the still

poorly understood driving forces for helical assembly, and 2) tune the

electronic properties of conjugated polymers.