By Divya Abhat

In the world of materials science, researchers are constantly seeking new ways to create more efficient, durable, and adaptable materials. One promising avenue is the study of bottlebrush block polymers, a unique class of macromolecules that self-assemble into intricate nanostructures. Tim Lodge and Frank Bates, both Regents Professors at the University of Minnesota’s College of Science and Engineering, and their teams have been at the forefront of this research, uncovering new possibilities for these polymers and their applications.

At its core, a polymer is a long chain of repeating molecular units. These molecules—often thousands or even tens of thousands of units long—make up everyday materials like plastics, rubber, and fibers with properties that can be tuned by adjusting the chemistry and structure of their molecular components.

Among polymers, a particularly interesting category is block copolymers, which consist of two or more chemically distinct polymer chains connected in a single molecule. These materials self-assemble into specific structures, much like how soap molecules arrange themselves in water. “There are a large number of different ways these things can pack in space,” says Lodge, “and we’re far from exhausting all the possible ways they can pack together.”

The Unique Value of Bottlebrush Polymers

The Unique Value of Bottlebrush Polymers

Bottlebrush polymers, unlike traditional linear polymers, have a central backbone with densely grafted side chains extending outward, resembling the bristles of a bottlebrush. When incorporated into a block polymer, this unique architecture provides two key advantages. First, the side chains push against each other, stretching the molecule outward and allowing for larger self-assembled structures.

“What that means in practice is that the size of the domains that you would get after self-assembly could potentially be much bigger, like a 100 or 200 nanometers,” says Lodge. “So, you could access a new range of length scale.” (Compare this to linear polymers, whose domain sizes are typically 10 to 50 nanometers.) This larger size is particularly useful for photonic materials, which manipulate light for applications like advanced optics and sensors.

Second, bottlebrush polymers reduce entanglement, a common issue in traditional polymers where the flexible coils can get tangled together—much like long strands of cooked spaghetti—restricting their ability to move. Bottlebrushes, however, are thick and, as a result, don’t wrap around each other as much. “So even though their absolute molecular weight can be much bigger, they are much more rapid in their ability to move,” says Lodge. This ease of movement helps them form structures in a practical timescale—making them valuable for biomedical applications, where soft, flexible materials are needed for tissue engineering and implants.

A Breakthrough in Self-Assembly

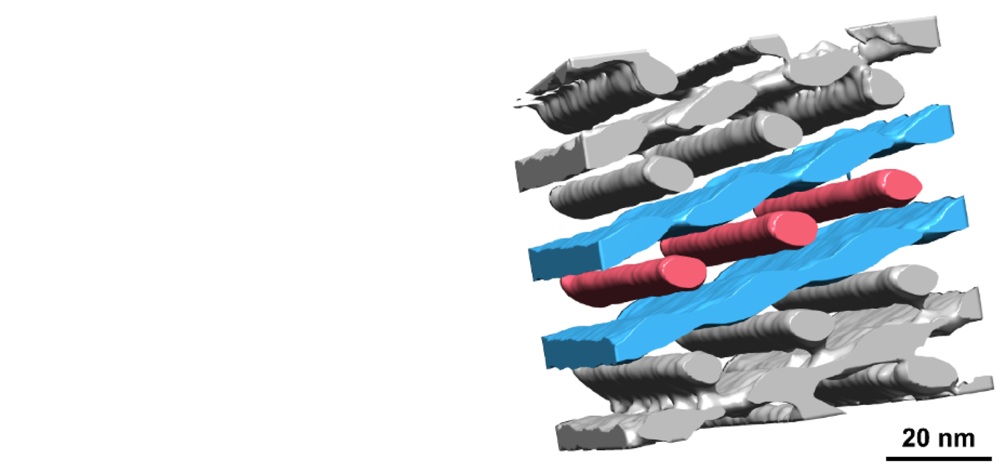

Despite their promise, bottlebrush block copolymers have typically been limited to forming only two basic shapes: stacked layers (lamellae) or tightly packed cylinders. This has restricted their use in applications that require more complex, interconnected structures.

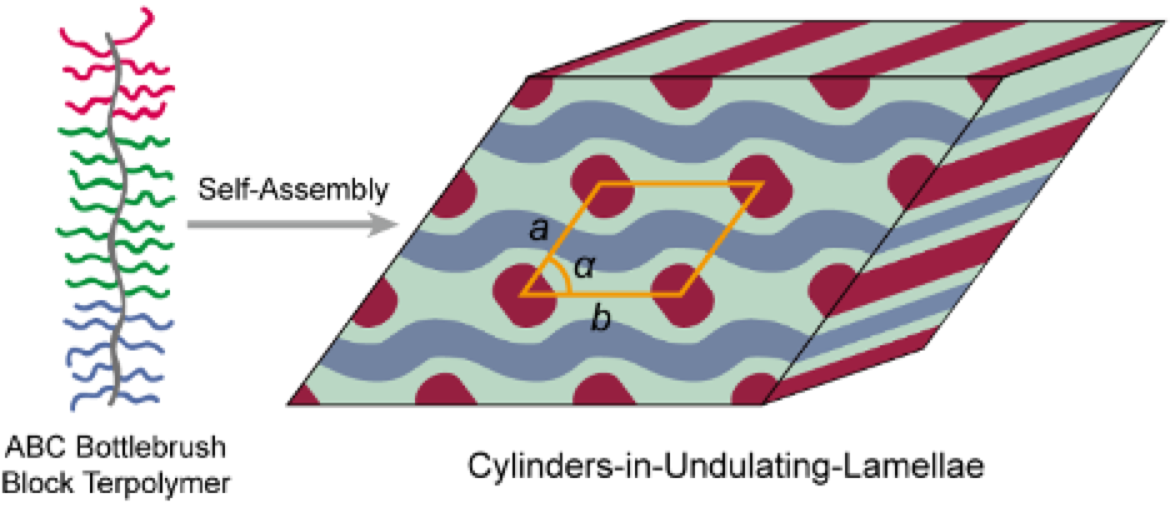

The Lodge/Bates team set out to change that by introducing a third polymer component into the mix to explore whether using three different blocks would lead to new structures. This approach, called ABC triblock terpolymer self-assembly, had been explored in simpler, linear polymers but was uncharted territory for bottlebrushes.

As part of their effort, the researchers focused on two specific chemical combinations:

1. PEP-PS-PLA – made of poly(ethylene-alt-propylene) (PEP), polystyrene (PS), and poly(DL-lactic acid) (PLA)

2. PEP-PS-PEO – made of poly(ethylene-alt-propylene) (PEP), polystyrene (PS), and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO)

They synthesized these materials using a method called ring-opening metathesis polymerization, which helps link the three blocks together. Using advanced techniques like X-ray scattering and electron microscopy, they then examined how these different chemical combinations influence the overall structure and organization of the polymer.

The results were striking. “What we discovered is that with these triblock bottlebrush polymers, we get a whole bunch of new structures that haven’t been seen before,” says Lodge.

To further study these polymers, the team—in collaboration with colleagues at the University of California Santa Barabara—used automated liquid chromatography to separate the polymers into different fractions. This revealed a variety of structures, showing that even small differences in polymer makeup can lead to significant structural changes. The group recently published its findings in the Journal of the American Chemical Society and ACS Nano.

Real-World Applications

Real-World Applications

Beyond their use in photonics, the flexibility of bottlebrush polymers opens doors in other fields. One promising area is biomedicine. For instance, these polymers can be made extremely soft—softer than conventional gels used in tissue engineering—making them ideal for implant materials, artificial cartilage, and even soft robotics. Moreover, bottlebrush polymers resemble natural biological structures. A class of molecules in the body called proteoglycans, which are found in cartilage and cell surfaces, naturally have a bottlebrush architecture—a similarity that perhaps suggests that bottlebrush polymers could be particularly well-suited for biocompatible materials that integrate seamlessly with human tissues.

“To date, application of bottlebrush polymers in medicine has been focused largely on sequestering pharmaceuticals for drug delivery,” says Bates. He anticipates that “advances in bottlebrush synthesis, and a deeper understanding of the interactions of this class of macromolecules with living tissue, will open up a plethora of new strategies for treating the consequences of injury and disease.”

Looking Ahead

Shuquan Cui, a postdoc at UMN and part of the team, has now synthesized over 300 different bottlebrush polymers, systematically mapping their behavior. “There are so many variables—how long each block is, how long the side chains are… there’s an almost infinite parameter space,” says Lodge. This work has laid the foundation for future innovations in materials science.

As for next steps, the team is eager to explore how these polymers can be fine-tuned for specific applications. What started as a theoretical exploration is now opening the door to a new generation of materials engineered from the molecular level up.